The plot summaries about for this film leave a lot to be desired. There is something distinctly airy-fairy about a line like “a boy who is believed to bring bad luck leads his family on a journey through Laos to find his family a new home”. Had I read that, I probably wouldn’t have bothered with The Rocket. Luckily I didn’t read one as soppy as that, and I took off on a whim to our cushy Palace Electric Cinema and saw it.

The plot summaries about for this film leave a lot to be desired. There is something distinctly airy-fairy about a line like “a boy who is believed to bring bad luck leads his family on a journey through Laos to find his family a new home”. Had I read that, I probably wouldn’t have bothered with The Rocket. Luckily I didn’t read one as soppy as that, and I took off on a whim to our cushy Palace Electric Cinema and saw it.

Now, I’m not saying there’s nothing soppy about this film, and that sentence is not an entirely inaccurate description of the plot. But this is a gritty, mucky and sometimes confronting story that just oozes the best and worst of humanity.

Set in the northern mountains of Laos, the story begins with the birth of that boy, Ahlo, who is saved from the tribe’s gruesome tradition of slaughtering the first-born of twins by his mother’s pleas against his grandmother’s judgement. The story cuts to him in early adolescence as his village is about to be flooded by the construction of a hydro-electric dam, and his mother is killed in a tragic accident. In the midst of his grief and confusion, he incurs the wrath of the village and the family finds themselves fleeing and beginning the search for a new home.

There is the risk with a story such as this that the inner turmoil of the boy could be overworked, bogging the story down in melodrama. But there is a great balance of pathos with movement, and the story almost plunges forward. There are moments of intense fear, beautifully crafted, and moments of sheer pleasure. This truly is the stuff of life.

The ever-present danger of unexploded weaponry, legacies from the Americans’ secret sojourn through the territory in the 1960s, is intermixed with idyllic settings and distinct twenty-first century technology like LED lighting, painting a picture of a society not entirely backward, but nonetheless held back by its history.

The success of this story really stands on the back of a brilliant performance by Sitthaphon Disamoe, whose energy is magnificent and never falters. The ten year old certainly earned the Best Actor Award he picked up at the Tribeca Film Festival.

This is genuinely one of the best Australian films I have ever seen, and if this is any indication of the direction our film industry is going, I think there is a bright future ahead.

Tags: Bunsri Yindi, Kim Mordaunt, Laos, Loungnam Kaosainam, Red Lamp Films, Sitthiphon Disamoe, Sumrit Warin, The Rocket, Thep Phongam, TriBeCa Film Festival

So now I’ve seen two films in a row that have mucked around with conventional plot structures and I’m starting to wonder if it’s something to do with me! Am I a little too conventional? Or should I just pull my head in and remember that a sequence of two maketh not a pattern.

So now I’ve seen two films in a row that have mucked around with conventional plot structures and I’m starting to wonder if it’s something to do with me! Am I a little too conventional? Or should I just pull my head in and remember that a sequence of two maketh not a pattern.

Tabu is the heart-warming story of a woman born in Portuguese Africa before a struggle for independence, but it begins by introducing her in her declining years. As the film began, in its rather confusing state, and focused on this poor woman’s dementia, I wondered if it would meander as pointlessly as The Place Beyond the Pines. It didn’t. In fact, the story completely snuck up on me, and though the tension was built slowly, I found myself completely drawn into it. I had to know how this story would play out.

The characters were beautifully drawn, pawns in a political game over which they had neither any control nor any desire to exert control. It is set in modern Portugal and in the foothills of a fictitious Mount Tabu in an unidentified African colony. I could try to draw some significance by suggesting the location as Guinea-Bissau, since it is the only tropical candidate for a Portuguese African colony, but clearly the creators did not intend to make a direct correlation. The story concerns the lives of individuals in a colonial context, and though it centres on themes of colonialism, it is refreshing to engage from the perspective of the powerless colonists, rather than the powerless colonised.

Ana Moreira is particularly noteworthy, and she is supported by a strong cast. Henrique Espírito Santo gives the narration for a long part, and although it was not necessary to have narration and it felt occasionally forced, it did mark the film throughout and prevent us from getting too bogged down in the emotion. This is, after all, a film for provoking thought.

Themes of impotence are becoming somewhat de rigeur, perhaps, but there is something quite unique in the perspective of this film and it should be considered one of the better of them.

Tags: Africa, Ana Moreira, colonialism, Guinea-Bissau, Henrique Espírito Santo, Portugal

SPOILER WARNING: my apologies, but what I want to say about this film requires a spoiler, so if you’re going to see it, do so before reading, though I really wouldn’t bother.

I’m not quite sure what to make of

The Place Beyond the Pines. It’s not a bad film, really, but I did come to the end and wonder what it was I’d just watched, and why. I don’t insist that every story needs to have a point, a story can certainly be just a story, but I can’t help thinking that all the writer really wanted was that elusive excuse to kill a protagonist immediately after the exposition (the psychosis of writers’ innate desire to kill protagonists, though, is a subject for another post).

Said protagonist is, in this instance, Luke Glanton, a circus stunt motorbike rider played rather passively by Ryan Gosling, who discovers that the woman he had a fling with on his previous visit to an upstate New York backwater has given birth to his son. Quitting his job, he turns to robbing banks, which ultimately leads to his demise, and the rather flaccid cop who shoots him in the line of duty becomes the new protagonist. I couldn’t help but chuckle aloud when an inter title announced we were moving forward fifteen years and a pair of protagonists (the sons of the first two) emerged as a duo.

I’m not sure what I think, partly because this film does well what I think all stories need. It is driven by its plot, which is a tick, though the convolutions in that plot are are not really justified by what they return to the viewer who carefully follows them. It boasts some well developed and nicely performed characters, which is a tick, though none of the characters are very likeable, nor do they elicit enough empathy for me to care what becomes of them. The cinematography is beautiful and moody, which is a tick, but these lovely images don’t quite pull the disparate elements of the plot and characters together the way they should. And it has a subtle soundtrack that supports the mood, but doesn’t really take it anywhere new (not really a tick at all).

Really, this is a trilogy of short films with a contiguous plot. They might not be separable, as they share a single exposition, but they are three very distinct stories. I can’t be too harsh on the film because all three are interesting, but I’m not sure that they’re quite interesting enough for two and a half hours of slow-moving American angst.

And so what I’m left with is a film that I think I like, but I’m not quite ready to give it a tick. I guess what I fear most, though, is that I may write a little like this. My characters can be held aloof from their viewers and my plots aren’t always worthy of the effort required to follow them. I hope, therefore, that a decent number of people like The Place Beyond the Pines more than I do.

- Pierce Nahigyan has a very different response from mine, but makes a few good points (and also gives you a rationale for the title) in his The Place Beyond the Pines (2013) Review.

- Amanda Caldwell was able to see a point in the story, as she explains on Life with a Blackdog.

- The Lord of the Cinema doesn’t seem to quite pass an opinion in his review on At the Movies.

- The Place Beyond the Pines: A Review (pixcelation.com)

- The Place Beyond the Pines Review (chrismackinmusic.wordpress.com)

Tags: Ben Coccio, Ben Mendelsohn, Bradley Cooper, Darius Marder, Derek Cianfrance, Eva Mendes, Luke Glanton, Place Beyond the Pines, Protagonist, Rose Byrne, Ryan Gosling, Short film

I was really looking forward to seeing Lincoln. His figure looms large over American history, and the particular juncture at which he held office in American history makes his story ever more relevant to a broad international audience. So when I found it so disappointing, I decided to wait a while and process it more before posting on it. And it’s been a worthwhile exercise, even if only for the study of historical narratives.

I was really looking forward to seeing Lincoln. His figure looms large over American history, and the particular juncture at which he held office in American history makes his story ever more relevant to a broad international audience. So when I found it so disappointing, I decided to wait a while and process it more before posting on it. And it’s been a worthwhile exercise, even if only for the study of historical narratives.

What this film suffers from the most is trying to tell the whole story of Abraham Lincoln’s final, event-filled years. It’s a common mistake for makers of historical films; to attempt to cram into a film of a couple of hours the full breadth and depth of several eventful years. The first two scenes illustrate the problem with this film perfectly. We begin with Lincoln being treated as a major celebrity by loyal soldiers, who for some inexplicable reason quote one of the president’s speeches back at him. Granted it’s a great speech, but I’m not convinced he’d forgotten it and needed the reminder, nor am I enamoured of the pathetic doe-eyed image of the American soldier so besotted with the president as to do such a thing. This scene is followed by the one thing screenwright Tony Kushner made a perfect call on; to use Mrs Lincoln to humanise and ground the celebrity. Had the story been mostly told through her eyes or in her presence, it would have made a much stronger impact, it would have held together more consistently as a narrative. Mrs Lincoln plays a significant role as the story progresses, but this role is too small for the attempt to narrate and humanise what is otherwise a docudrama mainly suitable for a midday slot on television. And of course, it isn’t helped by the longish written history lesson viewers are subjected to before the first scene even begins!

Whatever the creators have failed at, they have at least put to rest the myth of Honest Abe. Instead, Lincoln is depicted as the consummate politician, manipulative and conniving enough to achieve his goal, demonstrating both his leadership and his conviction. The mythical hero of history is in this film depicted as we know modern politicians; distrusting of democracy and determined to do good in spite of democracy’s aversion to good. It is a demonstration of the futility of democracy to see Lincoln connive and subvert the democratic process, only to turn the accusation of these ‘evils’ against Jefferson Davis.

This paradox, though, leaves me a little confused. I am not sure if the creators intended to depict Lincoln as a hypocrite, because he is otherwise shown as the consummate hero. I’m no fan of Westminster democracies, nor of the American congressional system. Both are subject to extreme subversion (in fact without subversion they’re entirely dysfunctional), and I like the way this film depicts that. But I am not convinced this was the intention of the screenwright. Too often the system is praised. Too often these characters have me convinced that they believe in their democratic processes. At the end of the film, I remain unsure as to what is being communicated.

This is a valiant attempt to tell an epic story, but it is unfortunately clouded by too many spectres of issues: democracy’s flaws; racial equality; gender equality and power all get a run, but none of them quite come into focus as well as they ought, mainly because the central character is a hypocrite, and his hypocrisy is not quite justified (not in the context of the film, that is; the historical figure of Lincoln had very good reasons for his lying, cheating and scheming).

So despite some great performances from the cast, fine characterisation and a rich plot, I found Lincoln struggled to deliver on clarity.

I think the magic bullet, the thing that would truly make this American history come to life in film, would be for it to be created by a foreigner. Americans take either too emotional or too factual a view of their complex history, and as a result, they slim down their historical figures to two dimensions. A foreigner would have enough distance from the material (and from the mythology Americans have built up around their history) to do it properly, and avoid these pitfalls. It would require a sympathetic foreigner, so a Canadian probably wouldn’t do. I suspect that if the story of America’s biggest political hero were to be told by an Aussie or a Brit, they’d hit the nail on the head. For my money, Lincoln is too confused a film to be worthy of the praise it’s getting.

So as you look for great films on this period of American history, I think Django Unchained the better choice.

Tags: Abraham Lincoln, Daniel Day-Lewis, History, History of the United States, Jefferson Davis, Lincoln, Tony Kushner

I’ve never been a big fan of Quentin Tarantino‘s films. Most offend on my most cherished traditions of storytelling — character and plot — so I pay them less heed than I might otherwise do, but Django Unchained is a true exception. Sure, I liked True Romance, and Pulp Fiction isn’t without its charms. Inglorious Basterds is a fine piece of cinema too, but Django Unchained is a refined, glorious masterpiece. A film worthy of the attention Tarantino usually gets for the more flimsy of his work. I will give three reasons why I think this film alone is worthy of all the praise that has been lavished on Tarantino for all of his lesser films put together.

I’ve never been a big fan of Quentin Tarantino‘s films. Most offend on my most cherished traditions of storytelling — character and plot — so I pay them less heed than I might otherwise do, but Django Unchained is a true exception. Sure, I liked True Romance, and Pulp Fiction isn’t without its charms. Inglorious Basterds is a fine piece of cinema too, but Django Unchained is a refined, glorious masterpiece. A film worthy of the attention Tarantino usually gets for the more flimsy of his work. I will give three reasons why I think this film alone is worthy of all the praise that has been lavished on Tarantino for all of his lesser films put together.

First, it has a plot. And not just an “I need an excuse to shoot so many scenes of blood and gore” kind of plot. It has a narrative. As in its central characters have a context in which to be, and not a flimsy one, but a solid, relatable, engaging one. A slave — Django — is bought in Texas by an anti-slavery German bounty hunter for the knowledge he has of the bounty hunter’s target. In exchange for Django’s help, he agrees to free him and share his earnings. The two become friends and colleagues and the German learns the story of Django’s wife, and they set out to free her from slavery also.

Second, it has characters that speak like real people. Not all of them, mind you, but a whopping majority, which is more than can be said for most of Tarantino’s characters (it’s also more than can be said for half of the movies made in the United States in the last 50 years). Most of them tend instead to opt for trite one-liners or metaphors or abbreviations of concepts that are supposed to make us think they’re really cool, but these characters are so damn cool they don’t need the pretence and can speak in full sentences like human beings. I like that. It gives them depth and develops relationships and shows me people I can relate to.

Third and best of all, Django Unchained has that wonderful quirk of Tarantino’s; the ability to draw us into the violence as if it is the realisation of our deepest, darkest instincts. It’s the karma we westerners of the 21st century wish we could exact upon the evil of the past. The wish that we could punish slave-owners for their sins, or take revenge on Hitler or upon that bully who just wouldn’t let up. I think this is what has sold so many of Tarantino’s films (that and truly beautiful cinematography that doesn’t just glorify, but truly beautifies, violence), and why I’ve often been willing to forgive the lack of plot or the superficiality of the characters or the ridiculous illogicality of the combat. Someone who deserves to suffer the full force of their victim’s fury is getting even more than the full force of it. Payback’s not just a bitch, she’s a tsunami of violence, desolating everything in her path.

And while this has always been the element I’ve liked in Tarantino’s films, in this instance, he doesn’t sacrifice character and plot to deliver it. And that is why Django Unchained is the film that redeems his ouvre.

Tags: blood, Christoph Waltz, Django, Django Unchained, Film, Jamie Foxx, karma, Kerry Washington, Leonardo DiCaprio, Payback, Pulp Fiction, revenge, slavery, Tarantino, violence

This is a romance story for those who don’t tolerate a lot of nonsense. And it is seriously one of the best romance films I’ve ever seen.

This is a romance story for those who don’t tolerate a lot of nonsense. And it is seriously one of the best romance films I’ve ever seen.

We meet Patrick, played by Bradley Cooper, in a mental institution as his mother delivers a court order for his release. It is soon revealed that he was institutionalised with bi-polar disorder following an incident following his discovery of his wife’s infidelity. Now on a restraining order to stay away from her, he seeks to prove that he’s worthy of his wife’s love and trust through positive living and a few trite aphorisms.

Before long, he encounters Tiffany, a widow suffering depression with whom he strikes a strong and immediate bond. From there the plot is basically predictable; they fall in love, he denies it, eventually changes his mind, yada yada yada. But it doesn’t matter, because these characters are so strong. Characters like these are hard to come by. There’s something so much more genuine than the average romance film offers.

The characters with the apparent mental illness offer great insights into humanity, and those without a diagnosis are shown to waver in their ability to control their senses also. We need more stories that depict varying degrees of mental health, rather than the old paradigm of being either sane or insane. This film does it beautifully, and is well worth a look.

Tags: Bradley Cooper, Chris Tucker, Jackie Weaver, Jennifer Lawrence, Robert DeNiro

I’ve just been to see Les Misérables and it seems the angst-ridden trailers that I’ve seen everywhere for this film would have been sufficient. It seems the marketers were given very little to work with and all the best bits of the film were used in the trailer, so there’s not really a need to pop along and see it.

I’ve just been to see Les Misérables and it seems the angst-ridden trailers that I’ve seen everywhere for this film would have been sufficient. It seems the marketers were given very little to work with and all the best bits of the film were used in the trailer, so there’s not really a need to pop along and see it.

I really hate to say it, but it’s the Australasians that let the film down (yes, New Zealand, when he does badly, Russell Crowe is a Kiwi; we’ll only claim him as an Aussie when he does well). Hugh Jackman is a little awkward but tolerable; the problem is that whenever he’s on screen, I’m seeing Hugh Jackman do Jean Valjean, rather than seeing Jean Valjean. The awkwardness with which he carries the role just undermines the suspension of disbelief.

I fully concur with those who have criticised the choice of Russell Crowe for the role of Javert. He is not entirely inappropriate, but it seems that although he can hold a tune, he can’t hold both a tune and a character at the same time. I believe he could have carried the character well enough were this not a sung-through musical, and I also have a feeling that there is scope for a film version of Les Misérables adapted to prose rather than the musical, which doesn’t really do the story any favours.

The film does have a few redeeming points, though. Whenever Anne Hathaway is on screen, I forget the awkwardness of Jackman and Crowe; she is engaging and poetic in every sense. Edward Redmayne is likewise convincing as Marius, and his chemistry with Amanda Seyfried‘s adult Cosette is palpable. Along with Isabelle Allen, these performers almost manage to redeem the film from the clunky performances of the two Australasians commanding the big dollars.

Whatever its faults, this film does one thing particularly well, in my opinion; while most productions that I’ve seen, whether for stage or screen, position Les Misérables as a quintessentially French story, this film sets the story amidst the mere backdrop of revolutionary France, allowing the characters greater autonomy from their political circumstances. It is my opinion that the story would sit just as well in front of any struggle for independence and liberty. It would be as at home before the Battle of the Chesapeake, the Eureka Stockade, the Myall Creek Massacre or Tiananmen Square, because the focus in this story is the journey of the individual characters within a particular political context. And of course, this being a story originally written by a Frenchman, its French context is de rigueur.

And perhaps that’s the big thing to learn from this rather expensive mistake of a film. What the world needs is an adaptation that takes the story of Les Misérables and depicts some fictional Aboriginal characters going through the same experience in the lead up to the Myall Creek Massacre… with prose dialogue to ram home the point. I’ll take that one. Anyone want to pick up Tiananmen Square?

- One of the more interesting posts I’ve seen is Why I walked out of Les Miserables (telegraph.co.uk)

- A particularly entertaining rant from The Movie Mind

- And for a bit of contrast, this person seems to have liked Les Misérables (2012) (canadiancinephile.com)

Tags: adaptation, Amanda Seyfried, Anne Hathaway, Edward Redmayne, Eureka Stockade, French Revolution, Hugh Jackman, Javert, Jean Valjean, Les Misérables, Myall Creek Massacre, Russell Crowe, Tiananmen Square, willing suspension of disbelief

Stories can broaden your horizons or deepen your insight. Many of them fail to do either, and this is what I would call a dud movie, though my bar isn’t very high really; even Quantum of Solace broadened my horizons a little! It’s only occasionally that you encounter a story that so closely aligns with your own experience—whether in the abstract or in the literal sense—that you just find yourself completely immersed in it. I haven’t encountered it for some time, and I may have forgotten what it was like, because The Perks of Being a Wallflower just took my breath away.

Stories can broaden your horizons or deepen your insight. Many of them fail to do either, and this is what I would call a dud movie, though my bar isn’t very high really; even Quantum of Solace broadened my horizons a little! It’s only occasionally that you encounter a story that so closely aligns with your own experience—whether in the abstract or in the literal sense—that you just find yourself completely immersed in it. I haven’t encountered it for some time, and I may have forgotten what it was like, because The Perks of Being a Wallflower just took my breath away.

The story of a quiet kid with a troubled past who finds the beginning of high school difficult is hardly new; in fact it’s just about as cliché as they come, but this film provides such a rich backstory and such expertly-developed characters that there is no sense of the cliché about it. It doesn’t take this Pollyanna approach that fools us into thinking that everything will be alright, but it still takes a glass-half-full sort of attitude to life’s dark periods.

The cast, led by an older-than-his-years Logan Lerman, are each one perfectly cast and wonderfully directed. Emma Watson shakes off completely the stain of Hermione Grainger and is the glue drawing attention back to the somewhat depressed protagonist. They are immersed in a world of 1990s grunge-esque culture that doesn’t allow any room for stereotypes without banning them altogether.

The nineties is something of a nondescript decade. Its specific characteristics are not instantly recognisable, and because of a slowed birth rate in developed countries in the 1970s, there are a relatively small proportion of us who think of it as our coming-of-age era, making it an unpopular choice for writers of historical fiction. The decade was characterised by a nervousness that resulted from financial downturns and shifting cultural values. This was the first decade when a critical mass of westerners came to see discrimination on the basis of race, sex, sexual orientation or political alignment as intolerable evils, and actually ceased to tolerate them. It was a time of flux, and as such, it defies the kind of definition and clarity the preceding decades enjoy. Add to that the prevailing winds of artistic expression and fashion being a postmodernism that borrowed and redefined aesthetics and oeuvres from the past century, and it really isn’t an easy time to narrow down. The Perks of Being a Wallflower is, I think, the first film made after the nineties that depicts the decade faithfully.

And how! I was 18 again. I felt like I knew these characters and belonged in these spaces. And there was nothing so distinctly American as to be foreign, which really is an achievement for an American film.

The Perks of Being a Wallflower hits that amazing balance of being perfectly mainstream in aesthetic, but with those deeper qualities of impeccable characterisation, a thoroughly engaging story, and a deep moral purpose. And not your deep-as-whale-poo kind of deep; deep like plays-your-heart-like-a-violin deep. Most American films find these qualities elusive, and it is a great relief to enjoy an American film that takes storytelling seriously.

Tags: Emma Watson, Ezra Miller, indie, Logan Lerman, Stephen Chbosky, The Perks of Being a Wallflower

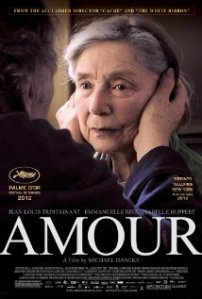

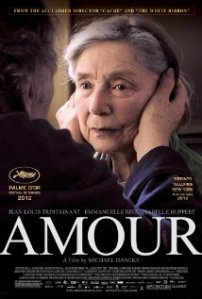

Amour probably won’t rate too highly on many people’s radars. It’s a little slow, the plot is a little controversial, but only if you have some knowledge of it, and it has no real pizazz to draw attention to itself. It doesn’t even draw you in terribly well, but nonetheless, I admire it deeply, and think it deserves more attention than it is likely to get.

Amour probably won’t rate too highly on many people’s radars. It’s a little slow, the plot is a little controversial, but only if you have some knowledge of it, and it has no real pizazz to draw attention to itself. It doesn’t even draw you in terribly well, but nonetheless, I admire it deeply, and think it deserves more attention than it is likely to get.

As a film, it is strongest in what I think is one of the most important aspects of all films; it takes the transcendent, the metaphysical, the magic of life, and plonks it down into the stuff of life, the grit and grime of reality where it rubs up against a higher meaning, a sense of purpose.

We meet the protagonists as they attend a recital at a theatre on the Champs Elysée. The elderly couple speak to the pianist afterwards, and they are clearly on familiar terms. From here, they return home to what seems a humble but comfortable existence. The following day, the wife suffers a stroke, which paralyses her on her right side, and their world is slowly changed. In fact, the gradual decline of her condition sometimes lulls the audience into a false sense of security as the couple adapt and change to accommodate alterations. The change, however, doesn’t cease.

If ever there was a good reason to make a slow film, this is it. The gradation of the woman’s deteriorating condition is carefully crafted to draw your attention away from the inevitable. The couple simply carry on with life and take control of whatever they can take control of.

I really wish more films were like this. There is no reason to divorce the transcendent from the prosaic, and here where they coexist they say something that few other mediums could put so eloquently. If the opportunity arises, see this film.

Tags: Emmanuelle Riva, France, French, Jean-Louis Trintignant, Love, Michael Haneke, Paris, prosaic, transcendent

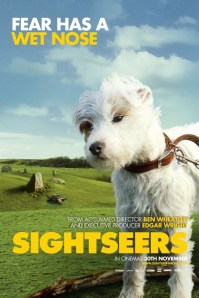

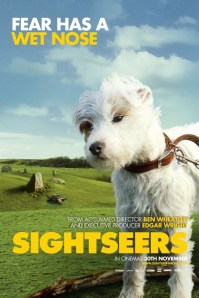

Sometimes a film starts out poorly, but improves out of sight by the end of the exposition. Such a film is Sightseers, which begins with an elderly woman making a miserable groaning sound for several minutes, while her daughter tries to get her attention. None too quickly the horrible old woman is removed from the scenario as her misfit of a daughter and her equally awkward boyfriend pack a caravan and head off.

Sometimes a film starts out poorly, but improves out of sight by the end of the exposition. Such a film is Sightseers, which begins with an elderly woman making a miserable groaning sound for several minutes, while her daughter tries to get her attention. None too quickly the horrible old woman is removed from the scenario as her misfit of a daughter and her equally awkward boyfriend pack a caravan and head off.

I must admit one thing that drew me to this film was the idea of Brits taking a caravanning holiday. I have always been curious to know the whys and wherefores of using a caravan to explore such a tiny island, and if there’s anyone out there with the same idea, I can tell you I have gained no insight into the phenomenon from watching this film.

What I did gain was a fantastically funny and gory 95 minutes. It was a little like a Tarantino film without all the corny one liners that really don’t work. And unlike a Tarantino film, it had characters. Real characters, with feelings and depth and backstories that you could only guess at. In some ways it was a bit like Shakespeare without the superfluous repetition, which of course brings us to the blood faster.

No, Sightseers is definitely not for children (not even my children!). It has one of the most hideous scenes of human mutilation I’ve ever seen in a film; and even this one has that wonderful capacity to combine gore and humour in the one image.

Don’t bother with Sightseers if you’re a little squeamish, but if you like a bit of blood with your humour, this is the film you’ve been waiting for.

Tags: Alice Lowe, Ben Wheatley, Canberra International Film Festival 2012, CIFF, Sara Stewart, Seamus O'Neill, Sightseers, Steve Oram

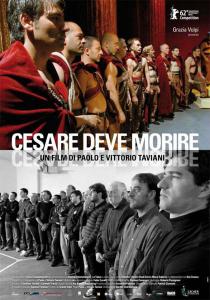

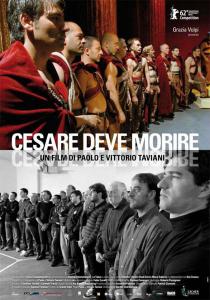

Well my first venture out into the 2012 Canberra International Film Festival was a little disappointing. Cesare Deve Morire (Caesar Must Die) was interesting, but I think it fails to stand as a cohesive whole, stumbling rather awkwardly from scene to scene.

Well my first venture out into the 2012 Canberra International Film Festival was a little disappointing. Cesare Deve Morire (Caesar Must Die) was interesting, but I think it fails to stand as a cohesive whole, stumbling rather awkwardly from scene to scene.

The film follows a group of inmates from Rebibbia prison in Rome staging Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. The inmates are introduced by their names, date of birth, sentence and crime before the play is cast, and we follow them through auditions, rehearsals and their performance.

Though it has its moments, and the performance itself appears compelling, I just didn’t find that connection that good films bring about with their characters. The film is slow, which can be tolerable, but a slow film shouldn’t lack detail. I really didn’t feel I got to know these characters, and when the credits rolled, I just felt it was about time.

I’m hoping for a better result from tomorrow’s CIFF films.

Tags: Caesar Must Die, Canberra International Film Festival 2012, CIFF, Cosimo Rega, Giovani Arcuri, Julius Caesar, Paolo and Vittorio Taviani, Rebibbia, Rome, Salvatore Striano, William Shakespeare

We’ve seen plenty of films centred on the victories of the Civil Rights Movement. Most are quite interesting but the bulk of them seem to float in the ether of the social and political significance of their subject matter, and don’t make a particularly smooth landing in the grit and grime of reality. That criticism can’t be levelled at The Sapphires.

We’ve seen plenty of films centred on the victories of the Civil Rights Movement. Most are quite interesting but the bulk of them seem to float in the ether of the social and political significance of their subject matter, and don’t make a particularly smooth landing in the grit and grime of reality. That criticism can’t be levelled at The Sapphires.

Inspired by the true story of the writer’s mother, who toured Vietnam during the American War, The Sapphires portrays three sisters and a cousin, young Aboriginal women who in 1968 are discovered by a drunk Irishman who can barely hold down a job but has a great passion for Soul music and recognises a talent. Auditioning for an American military talent scout, they are recruited and find themselves on their way to a war zone.

The story veers close to the heavy themes of racial discrimination, the Stolen Generation, and the moral predicament of the Western powers in Vietnam, but deftly avoids wallowing in them, instead focusing on the narrative of a family. It is remarkably how carefully balanced this story is, since it could so easily drop into a tirade on the heavy themes it skirts, but instead focuses on the triumph of hope and perseverance.

The Sapphires is distinctly the product of the early twenty-first century. It looks back at this period as a critical juncture in world history, a point when the usual shift in cultural values across the western world took on seismic significance and fundamentally altered the way we see things. And unlike most films that try to do this, it doesn’t preach, it doesn’t overstate the political and cultural significance of its subject matter. It just tells the story of five young people experiencing change at the crossroads of world culture. This is cinema at its best.

Tags: Australia, Chris O'Dowd, Civil Rights Movement, Deborah Mailman, Eka Darville, Jessica Mauboy, Keith Thompson, Miranda Tapsell, Shari Sebbens, The Sapphires, Tony Briggs, Tory Kittles, Vietnam, Vietnam War, Wayne Blair

There seems to have been a slew of films about journeys or pilgrimages from American film makers lately. Either that or I’ve just started noticing them. At any rate, I haven’t seen any as good as The Way.

The film, written by Emilio Estevez (who I had no idea could actually write), is the story of a man who finds himself walking El Camino de Santiago following the death of his son on the pilgrimage, and whereas most of these pilgrimage films I’ve been seeing are either a little light on character or a little too heavy, The Way has just the right balance, and drives forward beautifully, even surviving some very obvious product placement.

It could be a tearjerker if you’re that way inclined, but unlike others that could fit that bill, it doesn’t go out of its way to try to generate a deeper pathos than is necessary, and this is so very refreshing, especially from the Americans. This is the kind of story I want to be able to write.

Of course, the problem with pilgrimage films is that they give me itchy feet, but I always seem to be wanting to go somewhere, so I don’t suppose that matters much. Anyone want to join me in Spain in a decade or two?

- The Way (growingyoungereachday.wordpress.com)

- Sheen, Estevez write moving memoir (goerie.com)

Tags: Emilio Estevez, Film, Martin Sheen, Pilgrimage, Spain, United States, Way of St. James

Seems to me one of the most common accusations levelled at some films is that they’re predictable. And of course they are. Most films are made to be sold, and sold within a particular genre. Salmon Fishing in the Yemen deftly avoids such categorisation, and is one of the best character-driven films I’ve ever seen.

Seems to me one of the most common accusations levelled at some films is that they’re predictable. And of course they are. Most films are made to be sold, and sold within a particular genre. Salmon Fishing in the Yemen deftly avoids such categorisation, and is one of the best character-driven films I’ve ever seen.

Of course the problem faced by film makers who choose material like this is how to sell it. Having seen clips for it, I mostly dismissed it, and only made the effort to see it when I had just seen a whole bunch of films and wanted another. It was not my first choice, but of all the films I’ve seen this week (and I’ve seen a lot more than usual this week), this was the best.

The story is centred on a couple of public servants who find themselves at the centre of an exercise in international relations. Emily Blunt plays a consummate professional who has mastered the art of eternal optimism. And Ewan McGregor plays an infinitely more staid and predictable realist. These two find themselves pursuing the whimsical dream of a Yemeni Sheikh, played engagingly by Amr Waked, to introduce the sport of Salmon fishing to his dry homeland.

The story charts an unpredictable course through the ups and downs of the project, but along the way the central characters, even the Sheikh to some extent, become intensely human as they navigate life. It sounds corny, I suppose, but this really is an intensely human story, with all the pathos you could wish for, and none of the schmaltz. How screenwright Simon Beaufort and novelist Paul Torday managed this, I don’t know, but I take my hat off to them. I wish I could be relied upon to write like that.

Salmon Fishing in the Yemen has become one of my favourite films, just like that.

Tags: Amr Waked, character-driven, Drama, Emily Blunt, Ewan McGregor, Kristin Scott-Thomas, Paul Torday, Salmon, Salmon Fishing in the Yemen, Sheikh, unpredictable, Yemen

The thriller has not been a genre that has appealed to me greatly, but over the last few years a few of them have started to change that. Wolf Creek was one of the first, and The Ghost Writer was probably the most recent to impress me. Swerve can now be added to that list.

The thriller has not been a genre that has appealed to me greatly, but over the last few years a few of them have started to change that. Wolf Creek was one of the first, and The Ghost Writer was probably the most recent to impress me. Swerve can now be added to that list.

Starting with an exchange of drugs and money that doesn’t go entirely to plan, mild-mannered Colin (David Lyons) gets mixed up in a web of deceit, corruption and tangled motivations that don’t just keep you on the edge of your seat, but also keep your mind on its toes trying to remember who knows what, who owes what to whom, and where stuff is. In fact, this web of complications is almost too tangled, but I think the film survives thanks largely to two brilliant central characters expertly portrayed by Emma Booth and David Lyons, neither of whom I’ve ever encountered before.

Several action scenes involving car chases and accidents exemplify the elegant simplicity in this film’s cinematography, and that’s no mean feat. Perhaps its thanks to cinematographer David Foreman‘s background in television, but the action is brilliantly pared back to ensure that the focus remains on the characters and their objectives, contrary to what a lot of film makers tend to do. This is absolutely essential for a thriller, otherwise all you get is stunts and acrobatics, which I find far less satisfying than the thrill of seeing characters I care about in danger. As a result, the film as a whole stands up against its complicated plot and the occasional continuity error.

The sense of fear is palpable, and the film maintains an ethereal atmosphere without losing its grounding. This one is worth watching over and over again.

Tags: Broken Hill, Craig Lahiff, David Foreman, David Lyons, Emma Booth, Ghost Writer, Indian-Pacific, outback, South Australia, Wolf Creek

I love when comedies turn into dramas without me even noticing. I felt the slightest pang of disappointment a few minutes into Le Chef, at the fact that it was looking like a romp, and I was thinking the characters wouldn’t develop a great deal. I was wrong. Before I knew it I was completely engaged with these two chefs, who seemed at first to be one-dimensional. And although the laughs just kept on coming, the two central characters raised the experience well above a romp into the realm of pure drama.

Le Chef begins with its central character, accomplished chef Jacky Bonnot (Michael Youn), moving from one job to the next because he can’t tolerate his customer’s choices. His partner, expecting their first child, finally impresses upon him the importance of having stability for the sake of the child, and he takes a job as a painter. His talents, though, are soon recognised by Alexandre Lagarde (Jean Renot), one of the finest celebrity chefs in France, and he leaves another job to take an unpaid internship.

Le Chef is not the best French film I’ve ever seen, but that’s a tough challenge. It lacks some energy at times, but overall, it is hilarious and fully engaging. I wish more films could strike that wonderful balance between what is funny and true characterisation.

Tags: Alexandre Lagarde, Chef, France, Hopscotch, Jean Renot, Le Chef, Michaël Youn

Taking Offspring Number One off to Manuka to get a bit of the benefit of having the French Film Festival in town was quite an experience! I haven’t been to this cinema in years, and it hasn’t changed at all (even the popcorn tasted like it might have been there since my last visit!). But this film made it all worthwhile.

Taking Offspring Number One off to Manuka to get a bit of the benefit of having the French Film Festival in town was quite an experience! I haven’t been to this cinema in years, and it hasn’t changed at all (even the popcorn tasted like it might have been there since my last visit!). But this film made it all worthwhile.

La Guerre Des Boutons (or The War of the Buttons for those who are too lazy to figure that out!) proved an excellent choice given that we don’t have time to see more than one this year. But really, how could you go wrong with any film in a French film festival?

The premise is simple; gangs of boys from two rival country towns in walking distance of each other elevate a long-standing tradition of conflict to all out war in which the greatest victory comes by the ceremonial removal of the buttons from the opponents’ clothes. It may not sound all that terrifying, but the wrath of a French mother towards a son returning home with no buttons is nothing to be scoffed at!

The film is a romp, but in that inimitable French style, the humour is offset by some brilliantly crafted characters, whose more human side is shown as the impact of the Algerian War is felt in the town. The balance between humour and the film’s more serious themes is impeccable, making La Guerre des Boutonsa film for all ages.

Tags: Algerian War, Alliance Francaise, Cinema of France, Eric Elmosnino, French Film Festival, Greater Union Manuka, Movies, Vincent Bres, Yann Samuel

Hugois a great film, although it is about half an hour longer than it needs to be and (coincidentally?) half an hour too sappy.

Set in Paris, it’s the story of an orphan in the care of his drunkard uncle, who undertakes his uncle’s work to remain in his home in

Gare Montparnasse, to avoid ending up in an orphanage. His home puts him in the perfect position to pilfer the bits he needs to continue his dead father’s work restoring an old automaton, but it also puts him at risk from the station’s other denizens.

The story is excellent, and the visual effects stunning. The characters are beautifully composed, and the whole film sings… as long as you’re patient. This film would have been so much better if it had been written by a Frenchman; its American screenwright, however, has seen fit to weigh it down with as much schmaltz as he could muster. It’s a shame, because it would be just about perfect without it.

Tags: Gare Montparnasse, Hugo, John Logan, Martin Scorsese, Movies, Paris, United States

Meryl Streep‘s magnificent Maggie Thatcher well and truly matches Helen Mirren‘s remarkable Queen. It helps, of course, that the script is so well written by Abi Morgan, but to humanise this incredible woman is a great achievement, whoever you give the credit to.

Of course, it is only her most obvious frailty that provides the window of opportunity. Morgan’s script capitalises on the ageing Thatcher’s senility, and I don’t think there is any other way really to bring the woman down to earth enough for an audience to relate to her as a character.

The film lacks some of The Queen‘s zing. It creates magnificent character, but because of its broad sweep, it fails to create such a clear focus and the character is only just enough to cover the rather flat narrative structure.

The Iron Ladyis a very good film, and one well worth watching. But just in case any of you Poms were thinking about it, I’ve now seen enough biographical films about your twentieth century politicians. They’re really not that interesting.

Tags: Abi Morgan, Biographical film, feminism, Helen Mirren, Iron Lady, Margaret Thatcher, Meryl Streep

Late though I might have been, I finally managed to take the kids along to see The Adventures of Tintin. They weren’t that interested at first, and I can understand why, since the marketing is targeted at a higher age group and is certainly intended to attract adults. And by the time we went, it was no longer showing at Limelight, and we had to settle for Hoyts.

I don’t know why I particularly wanted to see this movie, as I never read the comics or had any experience of it before, but the trailer had me enthralled, and I was really keen. Obviously, the usual problem with films that you’re really eager to see is that they fail to live up to expectations. Not the case with Tintin.

The characters are really engaging, especially the bumbling detectives who are simply the most hilarious of characters. Tintin himself is endearing in a very personable way, since he is admired by all the characters for his prowess, but is nonetheless genuinely concerned with other people’s welfare. He is, at the same time, subject to frustrations and these shine through with pristine dialogue and amazing animation.

I’m not normally a fan of animation that looks too realistic, I’d usually prefer cartoons to look like cartoons, but in this context it just works.

The Adventures of Tintin is barely a children’s movie; there is a fairly long-running theme of violence, but it is handled well, and though my daughters (age 10 and 7) tensed up a lot, I never felt uncomfortable with the level of violence they were seeing.

This is a great film, especially for its characters, but also for its excellent animation.

Tags: Adventure of Tintin, animation, comics, Edgar Wright, Film, Herge, Hoyts, Joe Cornish, Limelight, ship, Steven Moffat, Steven Spielberg, Tintin

The plot summaries about for this film leave a lot to be desired. There is something distinctly airy-fairy about a line like “a boy who is believed to bring bad luck leads his family on a journey through Laos to find his family a new home”. Had I read that, I probably wouldn’t have bothered with The Rocket. Luckily I didn’t read one as soppy as that, and I took off on a whim to our cushy Palace Electric Cinema and saw it.

The plot summaries about for this film leave a lot to be desired. There is something distinctly airy-fairy about a line like “a boy who is believed to bring bad luck leads his family on a journey through Laos to find his family a new home”. Had I read that, I probably wouldn’t have bothered with The Rocket. Luckily I didn’t read one as soppy as that, and I took off on a whim to our cushy Palace Electric Cinema and saw it.